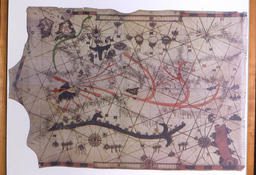

After the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70 ce, the Jews spread throughout the Mediterranean world. A major community eventually formed in the towns of the Iberian peninsula. The Sephardim, from the Hebrew for Iberia (“Sepharad”), played a prominent role in the culture and economy of both Muslim and Christian Spain and Portugal. (Item 11 is a chart drawn by one of a flourishing community of medieval Jewish chart makers.) But with the Christian reconquest of Spain, the victorious Catholic sovereigns, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon, decreed on March 31, 1492 that all Jews — young and old, male and female — were to leave Spain by the last day of July or convert to Christianity. Muslims were also expelled as part of the Spanish “reconquista.” An estimated 10,000 families chose to stay behind, many of whom embarked on a life of crypto-Judaism. Some 30,000 families (about 200,000 people) fled to foreign countries. The bulk of them crossed the border into Portugal, where another attempt at forcible conversion in 1497 pushed many out of Iberia altogether. Most Sephardim sought refuge within the Balkan and North African territories of the Ottoman Empire while others dispersed throughout the cities of the Mediterranean [11]. In later centuries, Sephardim moved to northwestern Europe and the New World [11, 15]. The several stages of the Sephardic Diaspora therefore constituted one part of the much larger Jewish Diaspora.

img/flat/exo12.jpg

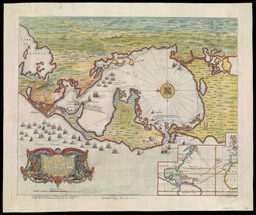

Judah Abenzara (Spanish, fl. 1490-1505)

[Portolan of the Mediterranean Basin with Atlantic

Europe and the Black Sea]

Facsimile of manuscript on vellum, 56 x 81.5cm

Alexandria, 1500

With permission of the Library of Hebrew Union College-

Jewish Institute of Religion

Overlay by Seth Klenk, 2001

The urban views in this section depict some of the cities in which Sephardic Jews lived. During the Middle Ages Seville [12] possessed a major Jewish population who freely observed their faith in the city’s twenty three synagogues. Over time, however, they were increasingly harassed by their Christian neighbors. In June 1391, an attack left 4000 Jews dead and forced many more to convert. This was a portent of the changes which culminated in 1492 with the expulsion of the Jews from Iberia.

map/32

Joris Hoefnagel (Dutch, 1542-1600)

Sevilla

Copper engraving, hand-colored, 33.1 x 47.5cm

From volume 4 of George Braun & Frans Hogenberg,

Civitates Orbis Terrarum

(Cologne: Gottfried von Kempen, ca. 1588)

Enggass Collection

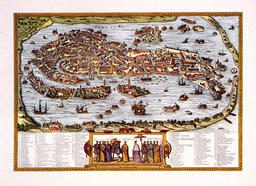

It is often hard to discern traces of the Jewish populations in urban maps, but they can be found. In this map of sixteenth-century Venice [13], the word “Ghetto” (number 144 in the directory at bottom of view) refers to the quarter in which the Jews were segregated. (Ghetto is a derivative of the Italian “ghettare,” meaning to throw or pour, because the area was previously the site of the city’s artillery foundry.) The term has since become synonymous with urban areas segregated by race, ethnicity, or economic status. This is its first known appearance of the word “ghetto” on any map. (See detail of upper left hand portion of view below.)

img/flat/exo14.jpg

[Bolognino Zaltieri (Venetian, fl. 1550-80)]

Venetia

Facsimile of a hand-colored, copper engraving, 33.9 x 47.9cm

From volume 1 of George Braun and Frans Hogenberg,

Civitates Orbis Terrarum

(Cologne: Peter von Brachel, ca. 1623)

OML Collection

Lured by freedom of religion and economic opportunity, a steady stream of Iberian “New Christians” began moving to Amsterdam [14] beginning by the 1590's. Once settled in their adoptive city, most reverted to Judaism. This return to the Jewish religion is not simply perceived as a continuation of ancestral ties that had temporarily been severed, but rather as a new beginning. It is telling, for instance, that many Jewish men adopted the names of the patriarchs at this time.

map/4731

Matthäus Seutter (Augsburg, 1678-1757)

Amsterdam

Copper engraving, hand-colored, 49.7 x 57.3cm

Augsburg: Tobias Conrad Lotter, ca. 1762

Smith Collection

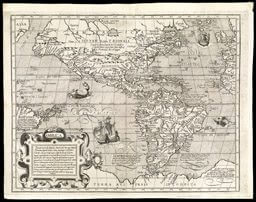

The seventeenth century was a period of violence and hope, of extinction and new beginnings. While the Inquisition succeeded in removing Judaism from virtually every corner of Spanish America [15], Sephardic Jews began settling in America’s Dutch and English colonies. In 1637, the first synagogue in the New World was established in Dutch Brazil in Recife (formerly Pernambuco). In 1654, twenty-three Jews left Recife for New Amsterdam (present-day New York City) where they formed the first Jewish community on North American soil.

map/346

Arnoldo di Arnoldi (Flemish, fl. 1590-1602)

America

Facsimile of a copper engraving, 36.4 x 47.0cm

Siena: Matteo Florimi, ca. 1600

Osher Collection

Overlay by Seth Klenk, 2001

After the Spanish Inquisition had established seats in Mexico City (1570) and Lima (1571), a third American inquisition was introduced in Cartagena de Indias [16, 17] to try all local offenses against the purity of the Catholic faith. Jewish residents nonetheless held secret religious services.

map/1879

Pierre Chassereau (French, fl. 1730-1750)

A New and Correct Plan of the Harbour of

Carthagena in America

Copper engraving, hand-colored, 41.9 x 50.6cm

London: Thomas and John Bowles, 1741

Smith Collection

map/1954

Violante Vanni (Italian, fl. ca. 1760-1770)

Plano Della Città,e Sobborghi Di Cartagena

Copper engraving, hand-colored, 25.8 x 18.9cm

From: Gazzettiere Americano (Leguria: Coltellini, 1763)

Smith Collection