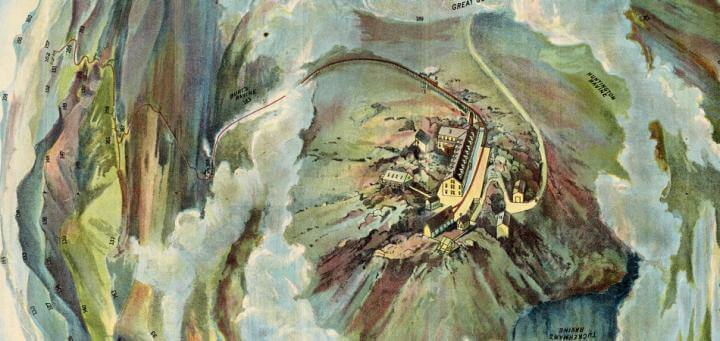

Birds-Eye View from Summit of Mt. Washington; White Mountains, New-Hampshire. In Bird’s Eye View from Mt. Washington New Hampshire.Boston: Passenger Department, Boston & Maine Railroad, ca. 1905

Like a “platform to New England,” the summit of Mt. Washington is the region’s crowning landscape jewel. It is the “highest,” most “noble,” “incomparable,” “marvelous,” ”absorbing,” and ”beautiful beyond description,” member of the “Presidential Range.” Boasting a singular view from the summit that is literally “out of this world,” so to say, the sheer magnitude of its impact is apparently downright dizzying and disorienting. But with the Birds-Eye View from Summit of Mt. Washington in hand, with which to measure, recognize, and craft the larger world, the vast stretches of apparently pristine wilderness become clear. To take in this view will be an experience like no other; a once in a lifetime moment brought to you by the trusty Passenger Department of the Boston and Maine Railroad.

There is something intrinsically alluring about seeing the landscape from a different perspective. From Google’s Streetview to the GoPro Camera’s fish-eye lens, the desire to capture the ordinary and everyday world and morph it into something extraordinary, to make it novel, new, and exciting, is a historically rooted tradition. At a time in history when travel, and the tourism industry were campaigning for a better world “out there,” maps like the Birds-Eye View from Summit of Mt. Washington, published in 1905 or later ~ the map and the pamphlet of which it is part are undated, but the text refers to events in Summer 1904 ~ and Edward Vischer and J. J. Cooper’s Panorama from the Summit of Mount Davidson, Washoe Range in Nevada (San Francisco, [1861]) transformed previously banal scenes into ones observed from innovative viewpoints that were enticing and refreshing. These maps are also snippets of social, political, and economic history; constructed out of the imagination and from ideas about how the landscape should appear and why. Seeming to present an unmediated 360-degree experience with the landscape, panoramic maps are intended to blur the edges between the realities seen by the eye and the desires of the mind’s eye, a reaction coached from the train’s loading dock to the top of Mt. Washington thanks to the pages of pamphlets filled with anticipated details enlivened by fantastical panoramic views.

Whether in the basket of a hot air balloon or strapped with gigantic wings, the front of the pamphlet housing the Birds-Eye View from Summit Mt. Washington creatively suspends the viewer in air as it imagines the panoramic view from the summit. The warped and almost ocular like map of Mt. Washington and the surrounding landscape is actually a scene more akin to looking at Earth from an all commanding, divine, or supervisory perspective. This northerly anchored and unconfined visualization radiates topographic information from the summit, or focal point, like a swirling eddy of peaks, numbers, colors, and clouds. Distant mountains are given numbers with corresponding names tallied outside the frame like itemized grocery lists for the viewer’s consumption. Emerging from the background like the red vein of an eye, the railroad snakes its way through faded towns as it rises above the clouds, puffing its way to the top, completely uninhibited. Although oriented to North, there are no scales, instructions, or legends, but rather the map is intended to be easily referenced from atop the summit of Mt. Washington while looking in any direction. It is a scene not intended to inform the viewer about crucial or navigable cartographic information, but one meant to be regarded for its aesthetic value (Evans 2011, 49). It is a view to get lost in; one where worries, like the horizon, just simply disappear.

Although panoramic maps are more extreme examples compared to the subtler horizon of the Bird’s-Eye Map of the White Mountains, published by the Boston and Maine Railroad slightly earlier, in about 1900,

the function of each map in the genre was still the same: to reinterpret the landscape. By using “realistic” renderings of places and spaces familiar to the average American, these maps were not only pleasing visually, but emotionally and imaginatively, as well (Schein 1993). Less about cartography and more about the pictorial experience, panoramic or bird’s-eye-view maps were designed to be both convincing and manipulating as they worked to promote and construct a record of the landscape devoid of life’s unsavory bits into places more pleasing; an abstracted and alternate reality as seen from the most privileged of vistas.

Further Reading

Byerly, Alison. 2007. “‘A Prodigious Map beneath his Feet’: Virtual Travel and the Panoramic Perspective.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts 29, no. 2-3: 151–68.

Evans, Robert. 2011. “A Bird’s-Eye View of Modernity: The Synoptic View in Nineteenth-Century Cityscapes.” Ph.D. dissertation. Carleton University.

Schein, Richard H. 1993. “Representing Urban America: 19th-Century Views of Landscape, Space, and Power.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 11 (1993): 7-21.

Megan G. Theriault (MA American and New England Studies; USM 2015)

October 2014

Prepared for ANE 633, “Mapping New England”