Ashely Towle, Ph.D., Lecturer in the Department of History and Honors Program, University of Southern Maine (written and published in May of 2022).

Listen to the Podcast:

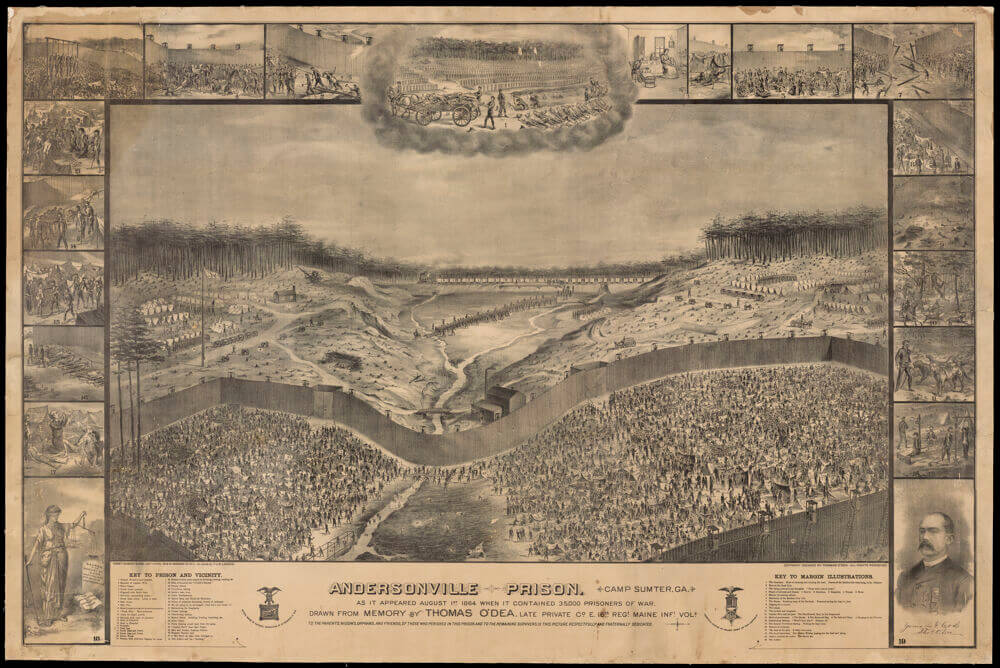

At first glance, Thomas O’Dea’s drawing of Andersonville Prison is overwhelming in its detail. Thousands of Union prisoners of war languish in the hot Georgia sun as more prisoners stream into the camp. Nineteen illustrations along the border depict significant happenings in the history of the camp. Constructed by the Confederacy in 1864, Andersonville was the most notorious prison camp of the Civil War. Over 13,000 prisoners died in the prison as a result of malnutrition, disease, and exposure. A veteran of the 16th Maine Volunteer Infantry, O’Dea was captured in 1864 and sent to Andersonville. He knew the horrors of the camp firsthand. In 1879, O’Dea began working on his illustration after seeing a picture of Andersonville in which the camp appeared “well regulated” with “nice wall tents erected in regulation style, giving the place an appearance of cleanliness and order.” O’Dea was outraged. He recalled, “in all the annals of civilization and barbarism, there never was, and I doubt never will be, such another place as ANDERSONVILLE.”1 Despite having no artistic experience, O’Dea spent over five years producing the realistic and detailed depiction of the suffering Union soldiers endured. He drew the entire image from his own memories which he said would be photographed in his memory until his dying day.

O’Dea’s rendering of Andersonville highlights the lethal consequences of the breakdown of prisoner exchanges during the war. Prisoner of war camps became increasingly crowded after 1863 when prisoner exchanges between the Union and Confederacy ceased after the Confederacy refused to treat Black Union soldiers as prisoners of war, and instead threatened to execute or reenslave them. The Confederacy also returned paroled soldiers to active service, something Union commanders realized when they began recapturing the same men again in battle. In an effort to win the war and capitalize on their superior numbers, the Union stopped exchanging prisoners, leading to overcrowded camps as the war dragged on. The Confederacy feared that the mass of prisoners contained in Richmond, Virginia could be liberated too easily by approaching Union troops, plus, the rail lines around Richmond were overworked trying to supply soldiers and civilians in Virginia. Andersonville was supposed to be part of the solution. Located in rural Georgia, Andersonville was designed to hold 10,000 prisoners on sixteen acres of land. But as the war persisted, the camp became overcrowded with 33,000 prisoners and was enlarged to twenty-six acres, giving each captive a mere thirty-four square feet within the stockade walls. In O’Dea’s image, he includes prisoners excitedly discussing the return of prisoner exchanges–something that offered men hope that they might soon be on the other side of the imposing gates of Andersonville or at least find some relief from the claustrophobic and squalid conditions of the camp.

Largely understaffed and undersupplied, prisoners at Andersonville suffered from a lack of food, clean water, shelter, and medical care. Prisoners’ only shelters were threadbare pieces of fabric constructed into makeshift tents called “shebangs.” These tents litter the foreground of O’Dea’s image. O’Dea depicts the meager food that prisoners received. In one scene, emaciated prisoners divvy up tiny mounds of food that constituted their sustenance. In another scene, prisoners dig for roots in the swamp to use as kindling to cook their maggot-ridden rations. The camp lacked a clean water supply or proper sanitation, leading to rampant disease. Prisoners can be seen bathing, drinking, and washing their clothes in the stream running through the middle of the camp. O’Dea portrays the lethal effects of this poor sanitation and malnutrition in scene 4 where men display symptoms of various diseases such as scurvy and diarrhea. One of the border images (#2) showcases the lengths to which prisoners went to secure clean water. A man attempts to get a cup of water upstream, where the water was presumably cleaner. To do so, he reaches past the “Dead line”–a boundary made out of thin wooden stakes that prisoners were not allowed to pass or they would be shot by the guards immediately. The man is gunned down.

Unsurprisingly, death was an ever-present facet of daily life in the prison. Thirteen-thousand men died within the walls of Andersonville, a staggering forty percent of the total Union soldiers who died in prison camps. It’s no wonder, then, that O’Dea chose to have a depiction of the callous burial of the dead crown the image. Bony arms and legs jut out of a wagon laden with corpses awaiting burial in a mass grave. Behind the trench, rows upon rows of headboards mark the graves of thousands of others.

Finally, O’Dea’s image is an entry point into exploring how Americans, and veterans, in particular, remembered the Civil War. O’Dea began working on his image only a few years after the end of Reconstruction–a tumultuous era in which the Federal government attempted to rebuild the South but failed to establish a biracial democracy. Following Reconstruction, Americans North and South began to reunite, buoyed by a romanticized memory of the Civil War known as the Lost Cause. This inaccurate characterization of the war purported that both sides fought valiantly, neither side was wrong in the quarrel, and slavery was not the cause of the war. Many veterans, however, refused to buy into this remembrance. O’Dea produced his illustration to remind Americans of the horrors of the Civil War. It flew in the face of this reconciliationist sentiment. During the war and for years after, Northerners consistently dragged up the specter of Andersonville as a symbol of Southern barbarity. But interestingly, O’Dea’s image is not merely an indictment of the South and the brutality the Confederacy inflicted on prisoners of war. In the lower-left margin image, O’Dea also condemns the Federal government. A blindfolded Justice holds a set of scales tipped in favor of war bonds, rather than Union soldiers in POW camps. O’Dea charged that the Federal government was more concerned with winning the war and recouping their money than they were with the lives of prisoners of war. By halting prisoner exchanges to win the war, O’Dea accused the Federal government of sacrificing the lives of prisoners; something he hoped Americans never forgot.

O’Dea’s image resonated with Union veterans. Veterans organizations across the country purchased O’Dea’s print to hang in their halls and meeting spaces. One veteran and survivor of Andersonville noted that the print was “wonderfully true in detail and gives one an excellent idea of the surroundings of that horrible den which can never be described with justice by tongue or pen.”2 While language could not fully convey the misery of Andersonville, through his meticulous attention to detail and accuracy, O’Dea was able to capture the essence of the brutality of Andersonville through his drawing. At a time when veterans feared that their sacrifices had been in vain and that their harrowing experiences had been forgotten by the rest of the country, O’Dea’s image helped to keep the memory of Andersonville and all they endured alive.

To see the map in detail: https://oshermaps.org/map/56198.0001

1 Thomas O’Dea, O’Dea’s Famous Picture of Andersonville Prison, as it appeared August 1st, 1864 when it contained 35,000 prisoners of war. Graphic description of that famous locality, with explanation of key to prison and marginal scenes, (Cohoes, N.Y.: Clark and Foster Book and Job Printers, 1887), 4.

2 “In Worthy Hands,” Daily Inter Ocean, January 5, 1888.

To see the map in detail: https://oshermaps.org/map/56198.0001

Further Reading:

Benjamin G. Cloyd, Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory(Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010).

Adam Domby, “Captives of Memory: The Contested Legacy of Race at Andersonville National Historic Site,” Civil War History 63, no. 3 (Sept. 2017): 253-94.

Charles W. Sanders, Jr., While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005).