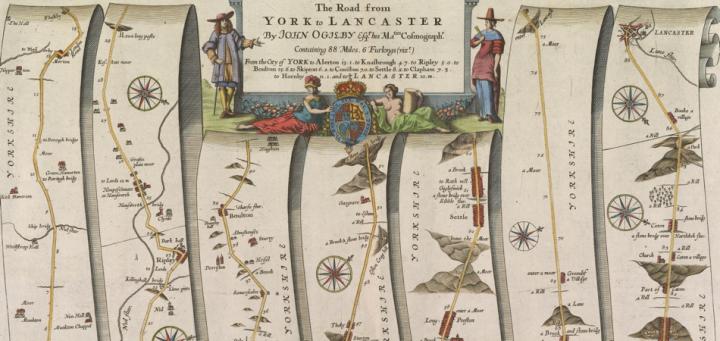

This strip map of the road between York and Lancaster, across England’s Pennine Mountains, was made as part of John Ogilby’s Britannia (1675), which systematically mapped the roads of England and Wales for the first time. This and the other maps in Britannia are visual itineraries, each depicting a single route from one town to another, and the landmarks along the way, mapped in long narrow strips. Although there is little resemblance between how we currently map roads and how Ogilby depicted them in Britannia, the atlas can be considered as one of the precursors to the modern road atlas because it provided the model by which roads in Britain would be mapped for the next hundred years.

Britannia was Ogilby’s brainchild. Ogilby (1600-1676) was a multi-careered man. He was originally a dancer who later turned to translating and publishing classical texts, before finally becoming a map publisher in his late sixties. He envisioned Britannia as the first of three volumes embracing the entire geography of England but his death prevented the completion of the other two volumes. To make Britannia, Ogilby commissioned several survey crews to measure distances along each route. Besides providing the first systematic documentations of British roads, Britannia is important for its consistent use of the statute English mile of 1,609m (1,760 yards, as defined in 1593) and abandoned the wide variety of customary miles previously used to record road distances and that varied in length from 1,500m to 2,100m (Zupko 1985). The result was to popularize the statute mile in English life (Hyde 1985, 1).

This particular map depicts the route from the city of York, in northeastern England, in the lower-left corner, to the city of Lancaster, in northwest England, in the upper-right corner. The map organized the route by representing the linear sequence of landmarks and other geographical features ~ such as churches, manor houses, and hills (especially in this map, as the road crosses the Pennines) ~ together with the measured mileages in between. Because the road is forced to fit linear strips, Ogilby added compass roses to indicate the road’s changing direction (Harley 1970, xv).

Although Britannia was a cumbersome volume that was impractical for actual travel, its maps proved so useful to navigating the complex road networks of England and Wales that many owners of the Atlas did not hesitate to cut out the relevant map before heading out on their journey (Van Eerde 1976, 137). In our modern world, dominated by GPS and a well-organized system of paved roads and highways, it is easy to overlook how innovative Britannia was for travelers in late seventeenth century. Britannia is an early milestone in navigation that eventually culminated in the current well of easy navigational information that we currently have today.

Further Reading

Harley, J. B. 1970. “Bibliographical Note.” In John Ogilby, Britannia, London 1675, v-xxxi. Amsterdam: Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. [OML facsimiles G1808 .O3 1970]

Hyde, Ralph. 1985. John Ogilby (1600-1675), Cosmographer to the King and Mapmaker Extraordinary. London: s.n. [OML reference GA793.6.O43 H9]

Van Eerde, Katherine S. 1976. John Ogilby and the Taste of His Times. Folkestone, Kent: Dawson. [OML reference Z232 O36 V35]

Zupko, Ronald Edward. 1985. A Dictionary of Weights and Measures for the British Isles: The Middle Ages to the Twentieth Century. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Ben Dombrowski (BA History; USM 2014)

December 2013

Prepared for GEO 207, “Map History”