Sir Ernest Shackleton first headed south in 1901, under Scott’s command [item 58]. Their personal differences began a heated rivalry that led Shackleton to organize three further expeditions on his own. On the Nimrod Expedition (1907–1909), Shackleton came within 97 miles (156 km.) of the South Pole. Considering his party’s failing supplies and exhaustion, Shackleton made the heartbreaking decision to turn back, having gone further south than anyone before. Because the pole had been reached by Amundsen and Scott in 1911–12, the goal of Shackleton’s Endurance Expedition (1914–1916) was to make the first transcontinental crossing of Antarctica, but was beset by disaster [item 61]. Finally, Shackleton embarked on the Quest in 1921 to circumnavigate Antarctica, but he died of a heart attack in January 1922 as the ship arrived at South Georgia [item 60]. This section uses some of the artifacts from Shackleton’s expeditions to gain insight to life on the ice.

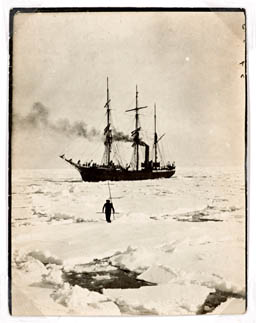

These pictures were taken of Shackleton during Scott’s Discovery Expedition, showing his arrival in New Zealand and then, during a reconnaissance mission, the Terra Novacrashing through the flows of pack ice in an attempt to reach land. About the latter, Shackleton wrote:

"It was not long before we were in the pack ice, and our stout ship was crashing through mighty flows and even then every now and again reeling back from the shock ... we were fortunate enough to penetrate farther east and discover new land ... On the 19th I was given a small party to make a sledge reconnaissance of the South west in order to see what chances there were for getting to the South by sledge journeys ... so we are now making preparations for the Southern trip ...”

map/4000070.0001

58. “Shackleton on arrival at Lyttelton”

ca. 1902

map/4000070.0002

58. “Terra Nova in Pack Ice”

ca. 1902

map/4000092

59. Frank Hurley and others

Photograph album, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1914–1917

This volume contains eight sepia-toned illustrations of Shackleton on his last expedition, including the Quest “Frozen in the Ice” and Shackleton’s burial cairn: “We left him under the Southern Cross.” This copy of the album was signed by Captain Frank Worsley.

map/4000078.0003

60. Southward on the Quest: Shackleton’s Last Antarctic Expedition

“Scala Souvenir,” ca. 1922

Shackleton’s Endurance reached the Weddell Sea in January 1915, to start his cross-Antarctic trek. But the ship was crushed in an ice pack. The party lived on ice flows until they finally reached Elephant Island in boats; from there Shackleton led an epic voyage of about 800 miles (1,290 km) to South Georgia in an open boat. After landing, the team had to hike over the mountainous terrain [see item 38 in section 5] before they reached a settlement and rescue. Amazingly every member of Shackleton’s party survived this 497-day ordeal.

map/4000021

61. Frank Hurley

The Endurance at Night, June 1915

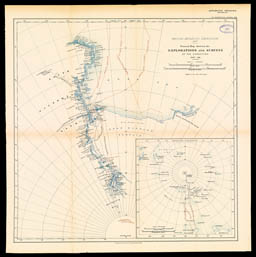

This map serves as an overview of Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition, including the routes taken by the Nimrod and the route that Shackleton pioneered party towards the South Pole. Shackleton added the routes of other explorers to put his journey into context.

map/4000036

62. Ernest H. Shackleton

“British Antarctic Expedition, 1907: General Map Showing the Explorations and Surveys of the Expedition, 1907–09”

From: Geographical Journal 34, no. 5 (1909): after 500

Shackleton wore this harness on the southward trek to the South Pole in 1909. Unlike Amundsen’s team, which traveled on skis with dog sleds, Shackleton had thought to use Manchurian ponies to haul their supply sledges. Unfortunately the ponies did not survive so Shackleton and his men had to pull their own sledges up the Beardmore Glacier themselves, for almost all of the 1,755-mile trek.

The harness saved Shackleton’s life on numerous occasions as his party negotiated the crevasse-seamed glacier. He remembered one occasion: “Just before we left the Glacier I broke through the soft snow, plunging into a hidden crevasse. My harness jerked up under my heart, and gave me rather a shakeup. It seemed as though the glacier were saying: ‘This is the last touch of you; don’t you come up here again.’”

map/4000090

63. Shackleton’s Sledge Harness, 1907–1909

Shackleton abandoned three crates of malt whisky beneath his hut at his camp on Ross Island in McMurdo Sound after the 1908–1909 winter. The crates were retrieved from the ice in 2007 by members of the New Zealand Antarctic Heritage trust; three bottles underwent scientific analysis in Scotland in 2011 in order to recreate determine the original recipe. Every detail, from the label to imperfections in the glass, was meticulously recreated.

map/4000029

64. Mackinlay’s Rare Old Highland Malt, 1909

A week after returning to New Zealand, Shackleton made this four-minute long recording, in which he summarized the achievements of the expedition:

“We reached a point within 97 geographical miles of the South Pole; the only thing that stopped us from reaching the actual point was the lack of 50 lbs. of food. Another party reached, for the first time, the South Magnetic Pole; another party reached the summit of a great active volcano, Mount Erebus. We made many interesting geological and scientific discoveries and had many narrow escapes throughout the whole time.”

map/4000091

65. Ernest H. Shackleton

Edison Amberol recording of Shackleton’s “My South Polar Expedition,” 1909

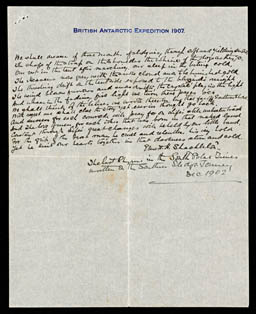

Shackleton voiced his feelings about the beauty and challenge of the Antarctic in this poem, annotated as, “The last Rhyme in the South Polar Times | written on the Southern Sledge Journey | Dec 1902.” (The expedition’s “newspaper” appeared as a typewritten manuscript issued in a single copy.)

“We shall dream of those months of sledging through soft and yielding snow.

The chafe of the strap on the shoulder the whine of the dogs as they go.

Our rest in the tent after marching, our sleep in the biting cold,

The Heavens now grey with the snow cloud anon to be burnished gold

The threshing drift on the tent side exposed to the blizzard’s might.

The wind-blown furrows and snow drifts, The crystal’s play in the light. . . .”

map/4000089

66. Ernest H. Shackleton

Autograph poem “L’Envoi,” ca. 1907

map/4000093

67. Shackleton’s Onoto patent self-filling pen, 1921

map/4000063

68. E. D.

Portrait miniature of Ernest Henry Shackleton, [1909]

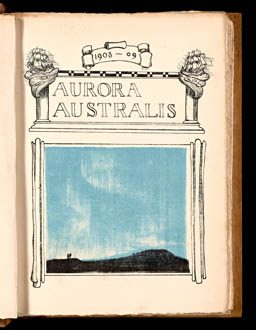

The first book printed and bound in Antarctica. Frank Wild and Ernest Joyce had taken a quick course in printing before their departure from England and, despite the cold and the cramped conditions of the hut at Cape Royds, they printed ninety copies in the winter of 1907–1908. The boards of the binding were made from empty wooden chests and the books were bound using old harness leather for the backstrip.

The book included articles and poems contributed anonymously by expedition members that were intended for an audience of friends at home. It was illustrated with lithographs and etchings by G. Marston, facsimiles of several of which are also on display: a view of the printing office, wedged between a large sewing machine and two bunk beds in a room measuring six by seven feet; a view of the kitchen (mess room); the wooden book cover, stenciled with “beans” on the front cover and “soup” on the back.

map/4000064.0002

69. Ernest H. Shackleton (editor)

Aurora Australis

East Antarctica: at the Sign of the Penguins, by Joyce and Wild, 1908

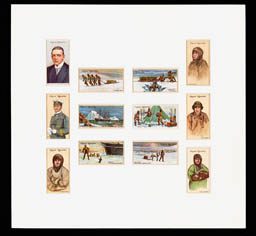

The eagerness with which the public followed the exploits of the polar explorers is shown by these collectible cards distributed by Player’s Cigarettes. The colorful chromolithographic illustrations were based on actual black and white photographs.

map/4000097

70. John Player & Sons

Cigarette cards: “Lieut. Sir E. H. Shackleton, C.V.O.” / “A Sledge Team” / “A Sledge Party Crossing a Crevasse” / “Captain Scott” / “Commodore Evans” / “The Terra Nova off Cape Evans” / “Setting up Camp” / “Dr. Wilson” / “Captain Gates” / “Demetri, the Russian Dog-Driver” / “Capt. Oates Exercising a Siberian Pony” / “Lieut. Bowers”

1915

In conjunction with the First International Polar Year (1882–1883), Adolphus Greely established a research station to collect astronomical and magnetic data at Lady Franklin Bay in the high Arctic. Only six of the twenty-five men survived their harrowing three years of isolation. Although the rescued men were initially treated as heroes, their fame was later tainted by rumors of cannibalism.

map/4000020

71. B. W. Kilburn

Stereoview from the Greely Expedition prepared for the Columbian Exposition

1893

map/4000054

Stereographic viewer