“’66 is the path of a people in flight, refugees from dust and shrinking land, from the thunder of tractors and shrinking ownership, from the desert’s slow northward invasion, from the twisting winds that howl up out of Texas, from the floods that bring no richness to the land and steal what little richness is there. From all of these the people are in flight, and they come into 66 from the tributary side roads, from the wagon tracks and the rutted country roads. 66 is the mother road, the road of flight.”

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, 1939

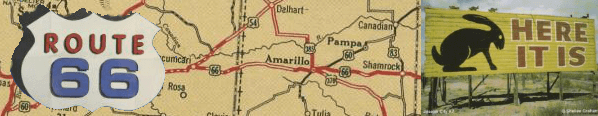

Over the years, Route 66 became an American icon, far more than a means to a destination. It offered the allure of the open road and all of the possibilities associated therewith. Businesses and popular culture latched onto the road’s growing popularity and by doing so provided additional layers of meaning to the layers of pavement. The Mother Road, America’s Main Street, the route to opportunities that lie in Southern California, the majestic landscape of the southwestern desert, all are associations brought to mind at the mention of the famous road. From Chicago to LA, businesses used the iconic appeal of Route 66 to draw in customers.

Today Route 66’s magic is still called upon to market goods and services. K-Mart has a clothing line bearing the name Route 66 and, despite decades of change, its advertising invokes the same dusty, open road that comes to mind when one reads Steinbeck’s description of the route in the 1930s.

The first major company to benefit by using Route 66 in its advertising was Phillips 66, an oil company that published maps using diverse images, all of which conjure a particular associations related to the road. The 66 was added to Phillips’ name in 1927, long before the road had risen to fame, when a car testing their new line of gasoline was clocked going 66 miles per hour on Route 66. Along with adding the number to its name, Phillips adopted a characteristic highway shield for its logo.

The earlier maps emphasize the road itself: the thrill of taking to the open road. This is most evident in the Iowa and Kansas maps which focus on the seemingly endless road stretching into the distance. Even the design on the Montana map promotes the sense that opportunity is just around the bend in the road. The way in which the landscape is untamed conjures ideas of an untamed wilderness just around the bend (although notably the top-fold Iowa map does have a scene that is reminiscent of 19th century pastoral New England landscape art). The road and the unknown, unseen land to which it leads is a recurring theme that does not entirely disappear even when the road itself is not shown in the later cover artwork.

The Utah map with a gas-station shows lights flooding only the building itself, allowing one to imagine a sense of isolation that many travelers along Route 66 likely felt when journeying great distances between small towns; the largely unpopulated Southwest can give the sense that a person is all alone in the world. One imagines that the lonely building symbolic of Route 66 exists in a familiar desert environment, the only mark of civilization for miles in any direction, visible at quite some distance like a beacon in the darkness. The coffee is probably bad having sat on a burner for hours since it was made, but at least it’s hot and the station is well lit, in contrast to the depths of night that seem to stretch on for eternity outside. There may or may not be anywhere to sit down, but there is hope for a break outside of the car, a bathroom, and a chance for some form of human interaction. Despite the fact that Route 66 does not run through Utah, the scene suggested by this image is one that would exist on 66 and it constructs an imagined bridge between 66 and the roads shown on this particular map and Phillips 66.