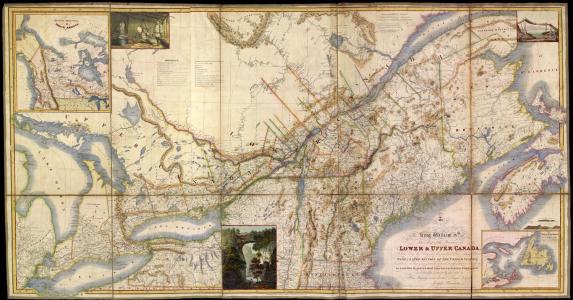

Between 1798 and 1842, Maine’s northern border was a point of hot contention between the English and the newly formed United States of America. The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolution, but did not clearly determine a northern boundary line separating the two governments. Following the war, the Commonwealth Massachusetts issued a series of land grants for its District of Maine, many of which the British had already laid claim to. In 1794, the two sides met to discuss the Jay Treaty, and agreed on a joint commission to determine the source of the St. Croix River, identified earlier in the Treaty of Paris. But the commission could not finalize the details of the river or the Passamaquoddy Bay islands. During the War of 1812, eastern Maine – Washington County, Hancock County and parts of Penobscot County – was dominated by the British, who intended to permanently annex the region into British North America. Then, in 1820, Maine achieved statehood, but had yet to figure out the northern border. In 1830, the dispute escalated to the point where commissioners frustrated with the dragging dispute, asked King William I of the Netherlands to arbitrate. King William was unable to reconcile the map with the treaty, however, and gave up within a year. He declared the treaty “inexplicable and impractical.” The dispute then took another turn with the Aroostook War, or Pork and Beans War, from 1838 to 1839. But, neither side wanted a war, and although militia units were called into position on both sides, they managed to avoid combat. The only casualties resulted from a lack of supplies and poor conditions. In 1842, the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of Washington finally settled the dispute, using the famous “Mitchell’s Map,” supposedly marked with a red line by Benjamin Franklin showing the true boundary.