There was much debate in Europe during the sixteenth century as geographers tried to incorporate the Americas within their existing world-view. Were they the islands off eastern Asia as Christopher Columbus had presumed (1) ? Or did they constitute an entirely “New World” (2) ? The lands to the south of the Caribbean were quickly promoted to the status of a continent. In 1507, the geographer Martin Waldseemüller called them America, after Amerigo Vespucci, who had falsely claimed in a best-selling account to have discovered the new continent in 1497. (This is present-day South America.) However, Europeans only slowly realized that the lands to the north, supposed to be Asian islands, did in fact constitute another new continent. Seeking a path through the islands in 1524, Giovanni di Verrazano ended up tracing most of the eastern coastline of this continent; but even then he misinterpreted the Carolina Banks as an isthmus, with the Pacific and the Indies beyond (3). Only in the second half of the century did public opinion settle on the existence of two new continents (5-7). The intellectual debate over the geographical character of the new lands was played out in printed maps. Having little, if any, access to the explorers’ own log-books and charts, which were kept secret, geographers constructed their maps from published accounts. They thus had great leeway for creativity (4) and for interpreting the voyages in accordance with their prior beliefs (3). The maps therefore comprised tentative and hypothetical outlines on which are hung place-names recorded by the explorers. A significant division can be seen in the place-names. Those derived from native sources were generally prefixed by “Land of …” (Terra de …). For example, Verrazano recorded the settlement and bay of Oranbega, which slowly mutated into the city and region of Norumbega, centered on the triangular estuary of the Penobscot River. In contrast, the names which Europeans imposed on the landscape were given without prefix: e.g., La Nova Franza, or Larcadia/Acadia. Ironically, the name Terra de Bacalaos/Newfoundland was actually derived from the Spanish or Portuguese word for cod fish, but it was thought as early as 1513 to have come from Native sources.

[The West Indies]

NOTE These other illustrations–together with a transcription, translation, and contextual history of the letter–are reproduced in a separate web-site prepared by the Osher Map Library. On his return to Europe in March 1493 from his first historic voyage, Christopher Columbus wrote letters announcing his success to his sponsors in the Spanish Court. One letter was passed on to a printer and quickly become a European bestseller. Several of the printers who then copied the letter added illustrations, which Columbus’s original letter had lacked. Those added to the Basel 1493 and 1494 editions include the first map of the New World. Lacking any of Columbus’s own maps and drawings, the anonymous Basel illustrator could make only highly stylized images. Columbus thought he had reached islands off Asia’s eastern coast, which he had claimed for Spain and which he had named. Item 1 shows a European ship among those islands and is an icon of Columbus’s success, not of actual geography. Components of the other Basel illustrations were patterned after previously published images of Europe and Asia. They represent: Columbus’s arrival; the fort he established; and, the sort of caravel in which he sailed.

ANONYMOUS

[The West Indies] In: Christopher Columbus, De insulis nuper in mari Indico repertis (Basel: Johann Bergmann, 1494)

Woodcut, 11.3 x 7.9 cm (image)

Osher Collection

[The Spanish Main]

This is the first printed map to show the actual geographical outline of the Caribbean, as Columbus mapped it in 1492-1503. It appeared in 1511, in a work which suggested that Columbus had in fact reached a “New World” rather than “the Indies.”

PIETRO MARTIRE D’ANGHIERA [PETER MARTYR] (Italian, 1459-1626)

[The Spanish Main] From: Legatio Babilonica Occeanea decas (Seville, 1511)

Facsimile of a woodcut, 19.5 x 28 cm, original in the Osher Collection

NOVAE INSULAE XXVI NOVA TABULA

Münster’s title (novae insulae/new islands) reflects the initial belief that Columbus had reached the supposed islands off Asia. After the extensive lands south of the Caribbean were recognized to constitute an entirely new continent–called America–Europeans still thought of the little known northward lands as being the Asian islands. In searching for a route through those islands in 1524-25, Giovanni di Verrazano ended up tracing the coast from Florida to Narragansett Bay. Even so, he identified a possible route to the Indies by reconfiguring the Outer Banks to be a sandy isthmus, with the Indian Ocean just beyond. Münster thus represented an ambiguous geography. By labeling both north and south together as Novus Orbis, Münster extended continental-status to North America. At the same time, he popularized Verrazano’s isthmus, showing it as connecting Terra Florida with Francisca (named for France).

SEBASTIAN MÜNSTER (German, 1489-1552)

NOVAE INSULAE XXVI NOVA TABULA

From: Münster, Geographia universalis …, 3rd ed. (Basel, 1545)

Woodcut, 26.8 x 34.3 cm

Smith Collection

From: Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Delle Navigatione et Viaggi (Venice, 1565)

This elaborate map illustrates the difficulties that European cartographers faced in using explorers’ reports. Gastaldi combined the geographical images of Verrazano and Jacques Cartier. Lacking any other information, he took Cartier’s furthest south in 1535 (Cape Breton) to be the same place as Verrazano’s furthest north in 1524 (Port du Refuge/Narragansett Bay). The result was that he eliminated the entire coast from Cape Cod to the Bay of Fundy. The islands to the east are Newfoundland (Terra Nvova, or Bacalaos). The few details in the interior are derived from Native sources (e.g., Terra de Labrador and Terra de Nvrvmbega) or are European impositions (especially La Nvova Francia/New France).

GIACOMO GASTALDI (Italian, ca. 1500-1565)

[New England and Eastern Canada] From: Giovanni Battista Ramusio, Delle Navigatione et Viaggi (Venice, 1565)

Woodcut, 27.0 x 37.2 cm

Osher Collection

TIERRA NVEVA

The coastline on this map is copied directly from its prototype, drawn by Giacomo Gastaldi in 1548. Gastaldi had in turn taken it from Cartier’s and Verrazano’s voyages. He did not however accept Verrazano’s idea of a western sea (3). Ruscelli modified the interior of the new continent: he hypothesized the presence of mountains inland; and, he joined the Hudson and St. Lawrence rivers, in accordance with Giovanni Ramusio’s idea of their common connection and source (4).

GIROLAMO RUSCELLI (Italian, ca.1504-1566)

TIERRA NVEVA

From: La Geografia di Claudio Tolemeo … (Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1561)

Engraving, hand-colored, 18.7 x 24.5 cm

Osher Collection

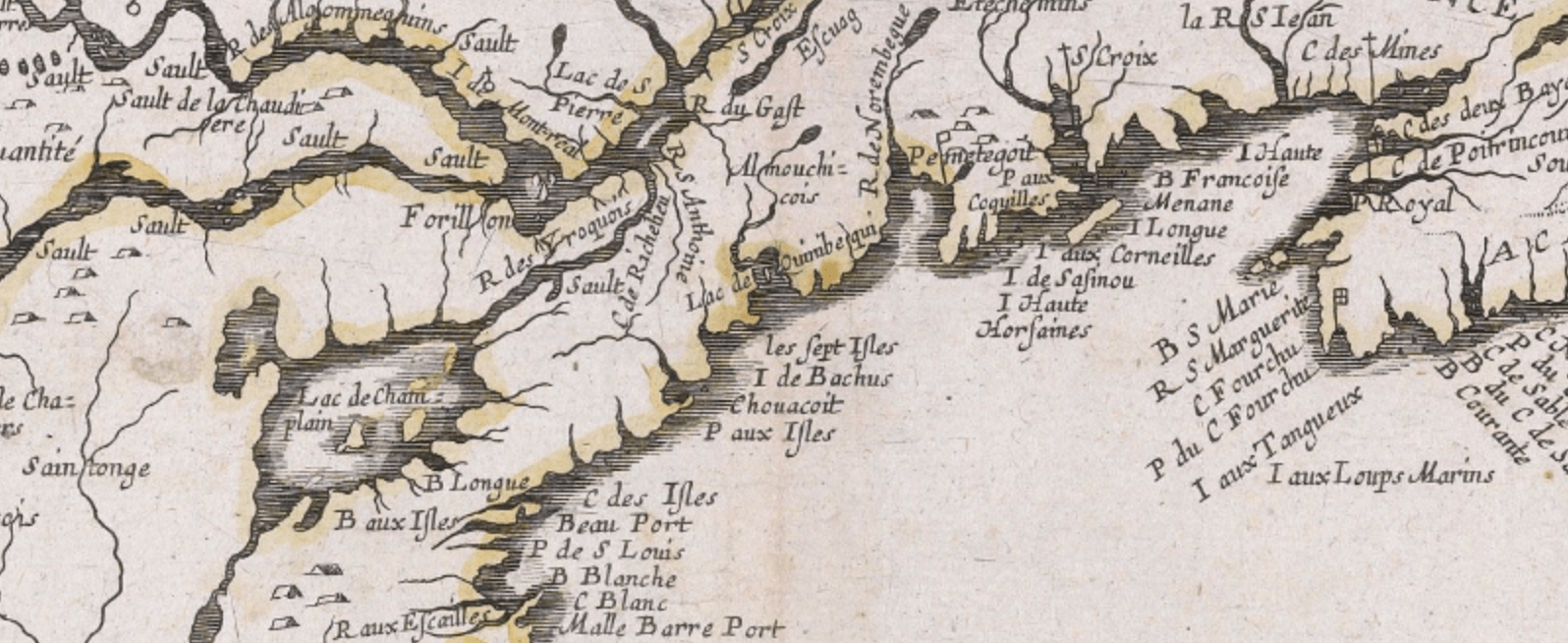

IL Disegno del discoperto della noua Franza …

Forlani offered another interpretation of North America’s geography. In particular, he literally mapped out his understanding of Cartier’s idea of ‘New France.’ Geographical ideas took precedence over actual geographical features. Forlani pushed apart Terra de Norumbega and Terra de Baccalos, both regions supposed to have been defined by the Natives. Between them he inserted La Nova Franza/New France, comprising Canada, and Larcadia/Acadia. From Cartier’s writings, Forlani knew that the core of New France was the St. Lawrence River. Rather than shift the region to encompass the actual river–whose actual geographical features were properly shown, but unnamed, to the north–he therefore invented a new river, which he labeled the river S. Lorêzo/St. Lawrence, within his idea of a region of ‘New France.’

PAOLO FORLANI (Italian, fl. 1560-1574)

BOLOGNINI ZALTIERI (Italian, fl. 1550-1580)

IL Disegno del discoperto della noua Franza …

Venice: Zaltieri, 1566

Engraving, 28.0 x 40.0 cm

Smith Collection

AMERICÆ PARS BOREALIS, FLORIDA …

De Jode gave a summary of the “North Part of America” as Europeans generally accepted it by 1600. He gave much space to the areas of Spanish and French colonial activity to the south and to the north. The little-explored regions between Florida and Nova Frãcia/New France, although extensive, required only a small part of the map. The north-south portion of his coastline, north of the prominent C. de las Arenas, represents the present-day middle states. The east-west portion–labeled Norombega–constitutes what is now New England, greatly reduced in area; the triangular estuary of the Penobscot is prominent. The rest of the map, from the Atlantic island labeled S. Brendan to the large land masses in the Arctic, is substantially derived from old European myths.

CORNELIS DE JODE (Flemish, 1568-1600)

AMERICÆ PARS BOREALIS, FLORIDA …

From: Speculum Orbis Terrae (Antwerp, 1593)

Engraving, 36.4 x 50.4 cm

Smith Collection