The entire process of the European exploring, settling, and naming of the New England coast and coastal regions was played out repeatedly, although with significant variations, when the English pushed into the interior of northern New England (32-33). From vague to precise geographies, from imposed place-names to negotiated settlements, the mapmakers and surveyors engaged in a geographical dance of place-creation with the local inhabitants, of both Native and European descent. This process was repeated in numerous districts; it is explored here in the context of northern Maine’s Moosehead Lake region. The new Americans expanded their interests within this land of potential and promise. They began by imposing an order on the land that paid little attention to Native names (34-35). After 1850, the opening up of the interior by the railroad led to the large-scale incursion of Americans looking to exploit the region’s timber and possible mineral wealth, or to exploit the region’s ecology for hunting and recreation (36-37). The naming of places was once again of concern as Lucius Hubbard and others tried to define the region’s ‘real’ place-names (38-39). Finally–at least for this exhibition–the arrival of the United States Geological Survey in the 1890s meant the end of negotiations and the official fixing of the regions place-names and topographies (40-48).

A New and Exact Map of the Dominions of the King of GREAT BRITAIN …

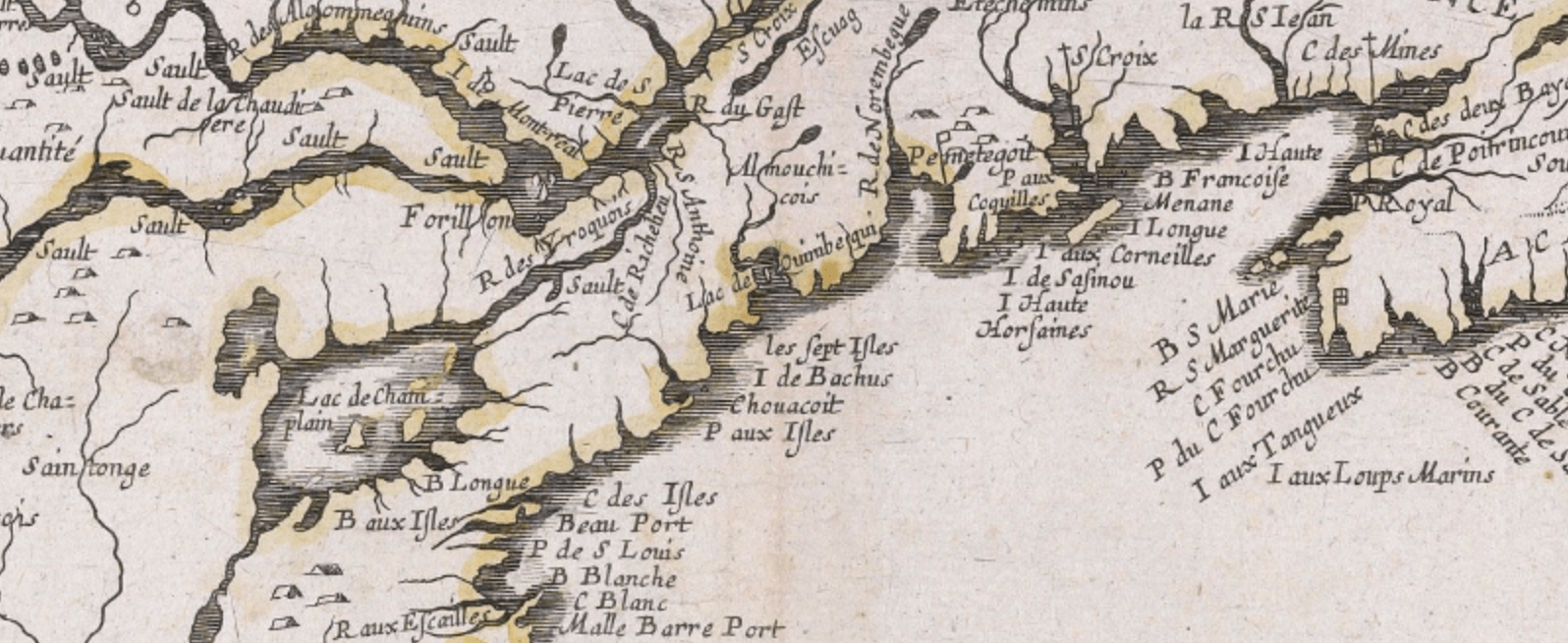

The vagueness of early European conceptions of the interior of North America are demonstrated by Moll’s map of the English colonies, originally published in 1715 (although the remarkable image of the beavers was copied from a French map of 1698). Once away from the coasts and the St. Lawrence, the interior of North America is shown as a vague jumble of rivers, lakes, and forests. It is a land of mystery and plenty, where beavers work industriously to build dams. Yet the beavers suggest the land’s potential for being improved, and for its plenty being increased, by human hands.

HERMAN MOLL (German/English, d.1732)

A New and Exact Map of the Dominions of the King of GREAT BRITAIN …

London, ca.1730

Engraving, hand-colored, 101.0 x 61.2 cm

Smith Collection

URL: www.oshermaps.org/map/632.0001

A Map of the Sources of the Chaudiere, Penobscot, and Kennebec Rivers

Col. JOHN MONTRESOR (English, 1736-1799)

A Map of the Sources of the Chaudiere, Penobscot, and Kennebec Rivers

Reduced facsimile of 1761 manuscript from F. H. Eckstorm, “History of the Chadwick Survey …,” Sprague’s Journal of Maine History 14 (1926): 62-89.

Hamilton Collection

PLAN of the Interior Parts of the Country from PENOBSCOT to QUEBEC

The English capture of Québec in 1759 prompted the English to establish an overland route from New England to Quebec City. Montresor (1760) and Chadwick (1764) followed long-established Native trade routes, one via the Penobscot River and Moosehead Lake, the other further east via Megantic Lake. Although both surveys were intended to define routes through the interior, rather than to map the interior itself, they mark the beginning of European/American attempts to come to terms with this vast region.

JOSEPH CHADWICK (English)

PLAN of the Interior Parts of the Country from PENOBSCOT to QUEBEC

Reduced facsimile of 1764 manuscript from F. H. Eckstorm, “History of the Chadwick Survey …,” Sprague’s Journal of Maine History 14 (1926): 62-89.

Hamilton Collection

T. N°. 2 R. 3 N.B.K.P. | Soldier Town

JOHN WEBBER (American, fl. 1820-1850)

T. N°. 2 R. 3 N.B.K.P. | Soldier Town

Neat copy of original field survey, 1833

Manuscript, ca.29.5 x ca.31.5 cm (image)

Hamilton Collection

Township Number 1, Range 10, W.E.L.S.

As a prelude to settlement, Northern Maine was divided into a series of townships, mostly formed by squares, each six miles on a side. The Moosehead Lake region was surveyed in the 1820s and 1830s. The first survey maps ignored the existing inhabitants and much of the landscape. They were generic: Soldier Town could be almost any other township! Only with the active use of the land–e.g., for lumbering (35)–did townships acquire any character as discrete places, a character embodied in new maps.

JAMES W. SEWALL (American, fl. 1850-1890)

Township Number 1, Range 10, W.E.L.S.

Updated 1878 copy of 1827 field survey

Manuscript, ca.39.5 x ca.39.0 cm (image)

Osher Collection

MAP OF MOOSEHEAD LAKE …

THOMAS SEDGWICK STEELE (American, 1845-1903)

W. R. CURTIS (American)

MAP OF MOOSEHEAD LAKE … by W. R. Curtis, C.E.

From: Steele, Canoe and Camera … (New York, 1880)

Lithograph, 59.9 x 47.0 cm

Hamilton Collection

Farrar's Map of Northern Maine . . .

Henry Thoreau published his first account of the Maine Woods in 1848. Yet few Americans could visit the region to emulate his travels and escape from urban life until the intrusion of the railroad in the early 1870s. Maps were major components of the guides that were produced–the first in 1874–as much to stimulate passenger travel on the railroad as to help tourists. The guides published by Steele and Farrar were two of the most enduring of the genre. Tidd based his map for Farrar on Curtis’s, but added some new data along the recently completed, and prominently marked, railroad. Note: such maps were published both in separate editions and in the guidebooks.

CHARLES A. J. FARRAR (American, d.1893)

MARSHALL M. TIDD (American)

Farrar’s Map of Northern Maine . . . By M. M. TIDD.

From: Farrar, Farrar’s Illustrated Guide Book to Moosehead Lake … (Boston, 1889)

Lithograph, 61.5 x 48.5 cm

Hamilton Collection

Map of NORTHERN MAINE

LUCIUS HUBBARD (American, 1849-1933)

Map of NORTHERN MAINE

Cambridge, Mass., 1899

Lithograph, 81.8 x 78.7 cm

Hamilton Collection

MAP OF MOOSEHEAD LAKE and NORTHERN MAINE

Although superficially similar to Steele’s and Farrar’s maps, Hubbard’s maps are significantly different in that they reflect a far more extensive experience with the Maine Woods and the Native peoples of the region. Hubbard had visited the region almost every summer during the 1870s, even before the railroad had arrived. Unlike the other guide maps, he based his own on a careful analysis of the Abanaki language and extensive interactions with local guides. That is, Hubbard’s maps constituted something of a compromise between the imposition of English names on the landscape and the existing cultural geography of the Native peoples.

LUCIUS HUBBARD (American, 1849-1933)

MAP OF MOOSEHEAD LAKE and NORTHERN MAINE

Cambridge, Mass., 1891.

Lithograph, 59.8 x 47.5 cm

Hamilton Collection

UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY

The initial topographic surveys in Maine (1898-1908) were of the populated coastal areas, except for a spur inland along the Kennebeck River (45). Most of interior Maine was not mapped thoroughly until after 1920, and the far north not until after 1945 (40, 43, 46). The government surveyors focussed on the physical features of the landscape: relief (shown in brown); hydrography (blue); and, in later editions, forest (green). Using guidelines established in Washington, the surveyors mapped (in black) only those cultural features that were part of American life: township and county boundaries, schools, roads, railways. The surveyors also used the property owners–mostly Anglo-Americans who had arrived after the railroad–as their sources for the names of rivers, lakes, and mountains. The result was the definition of an almost entirely American cartography of the region, one which erased many of the Abanaki place-names established by earlier, more locally committed mapmakers. UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, in cooperation with U. S. CORPS OF ENGINEERS (43, 46) and the STATE OF MAINE

All are color lithographs, ca.53 x ca.43 cm

All OML Collections (except 44: Osher Collection)

PENOBSCOT LAKE QUADRANGLE

PENOBSCOT LAKE QUADRANGLE N4545-W7000/15

Washington, DC: USGS, 1956

LONG POND QUADRANGLE

LONG POND QUADRANGLE

Washington, DC: USGS, 1924

PIERCE POND QUADRANGLE

PIERCE POND QUADRANGLE

Washington, DC: USGS, 1927

SEBOOMOOK LAKE QUADRANGLE

SEBOOMOOK LAKE QUADRANGLE

N4545-W6945/15 Washington, DC: USGS, 1954

BRASSUA LAKE QUADRANGLE

BRASSUA LAKE QUADRANGLE

Washington, DC: USGS, 1923

THE FORKS QUADRANGLE

THE FORKS QUADRANGLE

Washington, DC: USGS, 1907

NORTH EAST CARRY QUADRANGLE

NORTH EAST CARRY QUADRANGLE

N4545-W6930/15 Washington, DC: USGS, 1954

MOOSEHEAD LAKE QUADRANGLE

MOOSEHEAD LAKE QUADRANGLE

Washington, DC: USGS, 1922

GREENVILLE QUADRANGLE

GREENVILLE QUADRANGLE

N4515-W6930/15 Washington, DC: USGS, 1951