While North America lacked the historic castles, fortresses, and cathedrals of Europe, it did offer a varied natural landscape. Perceived as an untamed wilderness by the earliest settlers, by the mid-nineteenth century this same landscape was experienced as scenic and picturesque, thanks in large part to the paintings of the Hudson River School. The two main tourist routes were from New York up to Niagara Falls, and beyond, and from Boston into the White Mountains. A variety of fold-out maps and souvenirs promoted the several rail roads and their services to these tourist destinations, while the sites themselves were memorialized in an array of imagery.

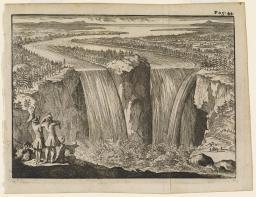

These prints document European and American fascination with Niagara Falls beginning with the written account by Father Hennepin, a Franciscan priest who was a member of LaSalle’s expedition in 1678. In spite of its inaccuracies, the image attributed to Father Hennepin was widely “borrowed” by other artists and engravers over the next two hundred years and came to signify the wondrous and sublime natural beauty of the North American wilderness.

img/flat/tou28.jpg

A Distant View of the Falls of Niagara

(1855). 18x22 cm.

Courtesy of Jerome and Monique Collins

img/flat/tou29.jpg

Louis Hennepin (1626-1701)

View of Niagara Falls from a New Discovery of a Vast Country in America

(London: for M. Bentley et alia, 1698).

Courtesy of Jerome and Monique Collins

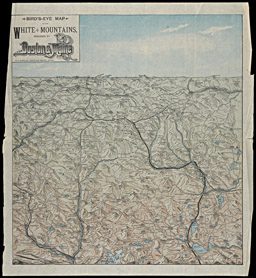

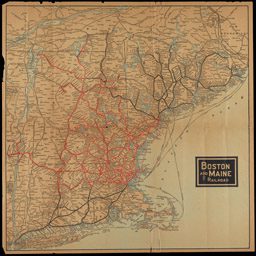

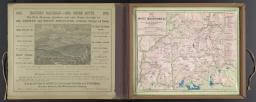

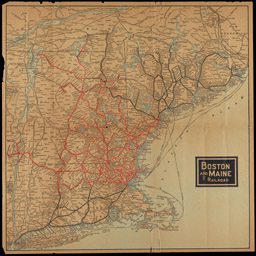

Typically, journeys into the White Mountains began in Boston, then the cultural capital of the United States. Boston catered to tourists with numerous large, opulent hotels and guide maps. Bostonians who could afford to escape the heat and epidemics of the city also took advantage of convenient rail access to New Hampshire and settled down for the summer in large hotels in the mountain passes, or “notches.” By the mid-nineteenth century a number of rail routes transported passengers to New Hampshire and Maine. To lure passengers the Boston and Maine Railroad promoted the region by developing their own illustrated tourist brochures and maps. Souvenir maps were also produced for tourists, such as the bird’s-eye view at far left. It names the mountain peaks that the visitor might recall and depicts the mountains in a visually pleasing form.

map/11724

Boston and Maine Railroads.

Among the Mountains, Boston and Maine Railroads and Connections

(Boston, n.d.). 57x78 cm.

Osher Collection

map/4792

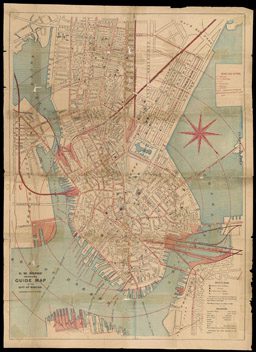

C.W. Hobbs’

Travelers’ Guide Map to the City of Boston

(New York, 1880). 65x46 cm.

Story Collection

map/15103

Rand Avery Supply Co.

Bird’s Eye Map of the White Mountains Reached by Boston and Maine R.R.

(Boston, n.d.) 40x40 cm.

Osher Collection

With the Hudson now being compared favorably to the Rhine, that river became the focus of the “American grand tour” for a newly emerging leisure class. The tour began in New York City before heading north and then east, on the newly invented steamships and railroads. Niagara Falls had developed into a major tourist attraction by the 1850s. Some travelers with the time and inclination continued on to Lake Ontario, Montreal, and Quebec. Further east, the White Mountains of New Hampshire became a center of more residential tourism. Railroads brought people to hotels in the mountain passes (“notches”) to stay for perhaps months at a time

img/flat/tou33.jpg

William S. Hunter, Jr. (1823-1894)

Chisholm’s Panoramic Guide From Niagara to Quebec

(Montreal: C.R. Chisholm, ca. 1868). 18 cm.

Courtesy of Robert Cotsen, M.D.

img/flat/tou34.jpg

John Disturnell (1801-1877)

Springs, Waterfalls, Sea Bathing Resorts and Mountain Scenery of the United States and Canada

(New York, 1855)

OML Collection

map/11720

Boston and Maine Railroads.

Text from Among the Mountains, Boston and Maine Railroads and Connections

(Boston, n.d.). 57x78 cm.

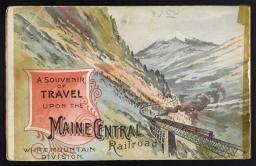

img/flat/tou36.jpg

Maine Central Railroad.

Through Crawford Notch of the White Mountains

(Boston, 1872). 10cm. With facsimile of verso image.

OML Collection

img/flat/tou37.jpg

Geo. K. Snow & Bradlee.

Relief Map of the White Mountains, published by Geo. K. Snow and Bradlee at the office of Snow’s Pathfinder Railway Guide

(Boston, 1872). Relief model, 22x27x3 cm, in case 24x29 cm.

Osher Collection

The views shown here were very popular on both sides of the Atlantic. With its Old World feeling, North American French culture, and dramatic views of the St. Lawrence, Quebec became a popular tourist destination in the nineteenth century. For some, it was the final stop of the Hudson River and Niagara Falls circuit. A cone of ice is formed each winter as the spray from the Montmorency Falls freezes in the air and builds up. The result is a natural toboggan slide. It continues to be a winter event for Canadian and American tourists to this day.

img/flat/unavailable.png

Quebec

(New York: d. Appleton & Co., 1872). 19x26 cm.

Courtesy of Jerome and Monique Collins

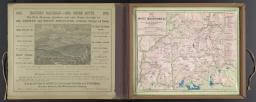

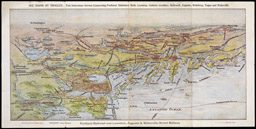

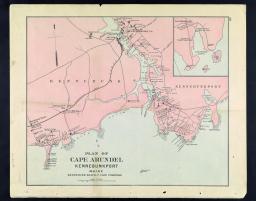

Like the White Mountains, Maine owes its reputation as a tourist destination to the construction of primary rail lines together with numerous spur lines to smaller inland communities by the Boston and Maine Rail Road. After the completion of a comprehensive network of rail lines after Civil War, Maine became relatively easy to access from across the eastern seaboard, from Philadelphia to Boston. Hotels and cottages sprung up along Maine’s southern and northern coasts to accommodate upper-class families who would arrive with their steamer trunks and servants in June and remain for the entire season. Item 36 is a wood engraving that depicts the summertime pleasures of the seaside as experienced in Kennebunkport and Old Orchard Beach. It was created by Harry Fenn, an English artist who also contributed to Picturesque America. This item accompanied an article in an 1887 issue of Harpers Weekly. For working class families, who typically did not have vacations, a leisure pursuit on Sundays might be a trolley ride to the end-of-the-line park like the Riverton Park and Cape Cottage Park and Casino listed in this 1887 trolley brochure.

map/11720

Boston and Maine Railroad

Osher Collection

map/12140

Portland Railroad Company

Trolleying through the Heart of Maine: Portland Railroad Lewiston, Augusta & Waterville Street Rt.

([Portland, Maine], [1900?]). 20x40 cm

Osher Collection

img/flat/tou41.jpg

J.H. Stuart & Co.

Plan of Cape Arundel, Kennebunkport, Maine, Kennebunk Beach, Cape Porpoise

(South Paris, Maine, 1891).

Courtesy of Jerome and Monique Collins

img/flat/tou42.jpg

Harry Fenn (1838-1911)

Around Kennebunk and Old Orchard Beach

(New York: Harper's Weekly, 1887). 27x38cm.

Courtesy of Jerome and Monique Collins

Given the long distances between major cities in North America, the transportation infrastructure was critical to the country’s development. But to negotiate the system required information. Some maps were produced specifically to inform Europeans of how they might ship freight, or themselves, across the Atlantic and across the American continent. Even then, detailed knowledge was required of the schedules of each form of transport. Detailed guides appeared even before the railroads, as with S. Augustus Mitchell’s 1833 map and time-table guide to the stage coaches, steam boats, and canal boats that already crisscrossed the eastern USA. With the vagaries of weather and potentially long layovers, it was not uncommon in this early period for foreign travelers to reserve twelve to eighteen months for their American tour east of the Mississippi. Such tours were dramatically reduced to about three to six months in duration when rail lines were first introduced.

map/2620

Thomas C. Keefer (1821-1915)

Mercator's Projection with the Great Circle Shortest Sailing or Air Lines Illustrating River St. Lawrence from Lake Erie to the Atlantic...

(Montreal: Canadian Commissioners of the Paris Exhibit, 1855). 58x89 cm.

OML Collection

map/3574

James Hamilton Young (fl. 1817-1866)

Mitchell's Travellers Guide through the United States

(Philadelphia: S. Augustus Mitchell, 1833). 44x56 cm. and 43x51 cm.

Osher Collection

img/flat/unavailable.png

Ismay, Imrie & Co.

White Star Line Royal and United States Mail Steamers (June 10, 1904). 31x49 cm.