Ocean liner décor was calculated to recreate the charms of an upper-class home—or at least one’s club—and to ignore the sea entirely. The Aquitania’s first-class drawing room [68] featured an oval dome with lunettes and lead mouldings and ornaments, Cuban mahogany doors and bookcases, a marble chimney piece, and walls “hung with blue tabourette silk, and . . . adorned with a collection of mezzotints of 18th Century beauties.” In season, the garden lounge [69] brimmed with flowers.

The Canadian Pacific’s Montrose [70] cabin-class dining room seems more Hogwarts than high seas, while the Majestic’s swimming pool is positively Pompeian [71]. Decorators were not afraid to mix and match, hence the juxtaposition of North African and Louis XIV flavoring aboard the Paris [72-73], and the Wild West influence of the Washington’s smoking lounge alongside the strangely unexotic “Chinese Room” [74-75].

The difference between the ritzy splendors of first- and second-class accommodations and those of the third class [76-78] would have been readily apparent to any of the wealthier passengers who ventured below for an evening of “slumming it” with the masses.

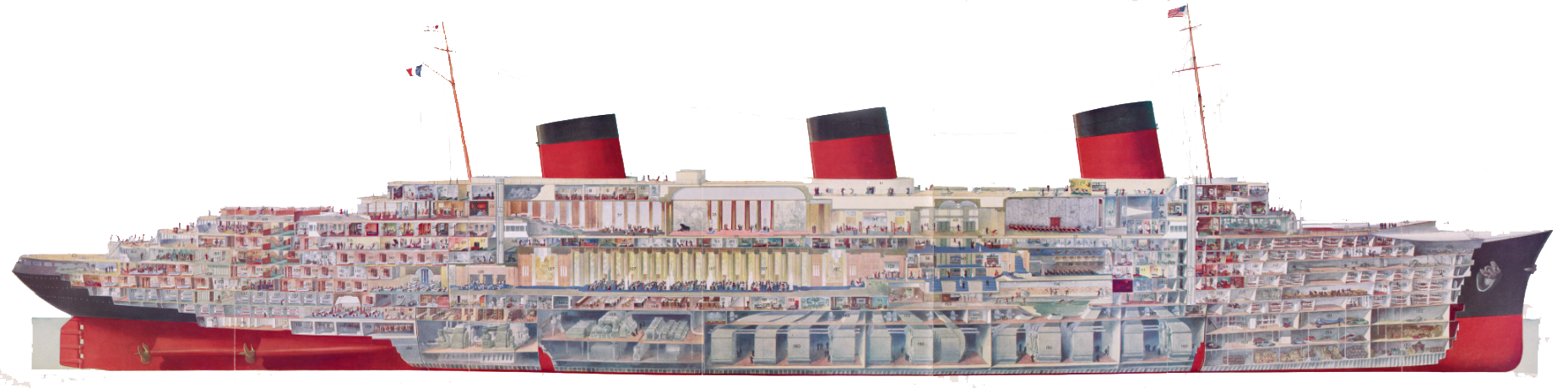

The art deco styling of the Ile de France set a new standard for passenger ship design world-wide. With its clean lines and emphasis on functionality, the “ocean liner style” helped popularize and disseminate the concepts of modernism. At the same time, the “Isodeckplan” was introduced to render ships’ accommodations in an elevated, three-dimensional view [86].

The modernist design and decoration of the Nieuw Amsterdam, which would not have been out of place at Rockefeller Center, was the subject of a lengthy article in the influential fine art magazine, The Studio [79].

“Hotelism is a modern disease that arrived with the steam-engine, a sort of artistic hydrophobia in that those responsible for the internal decoration of a modern liner are mortally afraid to leave any indication that the scenes of their efforts belong to an ocean-going vessel. Thus afflicted, they run amok with a rainbow and a few acres of gold leaf, trailing behind them a devastation that would have made Solomon in all his glory appear mean and dingy.” —C. R. Benstead, Atlantic Ferry, 1926