A. The Discovery Expedition (1901-1904)

After Cook and the U.S. Exploring Expedition [section 5], Antarctica appeared on maps through the nineteenth century, often tied as in previous centuries to South America yet graphically separated as a distant and forbidding place [items 42–43]. The outline of the icebound continent was steadily updated through the rest of the century [item 35 in section 4]. Antarctica once again became the center of attention at the start of the new century, when the dramatic race for the North Pole [section 3] sparked a similar race to reach the opposite, South Pole. Although the race was won in 1911 by a team led by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (1872–1928) [items 44 and 46], it is the ill-fated exploits and stiff-upper-lip courage of the British army captain, Robert Falcon Scott (1868–1912), that dominates public memory [item 52]. Scott led two expeditions, both funded by the Royal Geographical Society, which was also a major publisher of exploration accounts and maps of Antarctica [items 45 and 46, and item 62 in section 7].

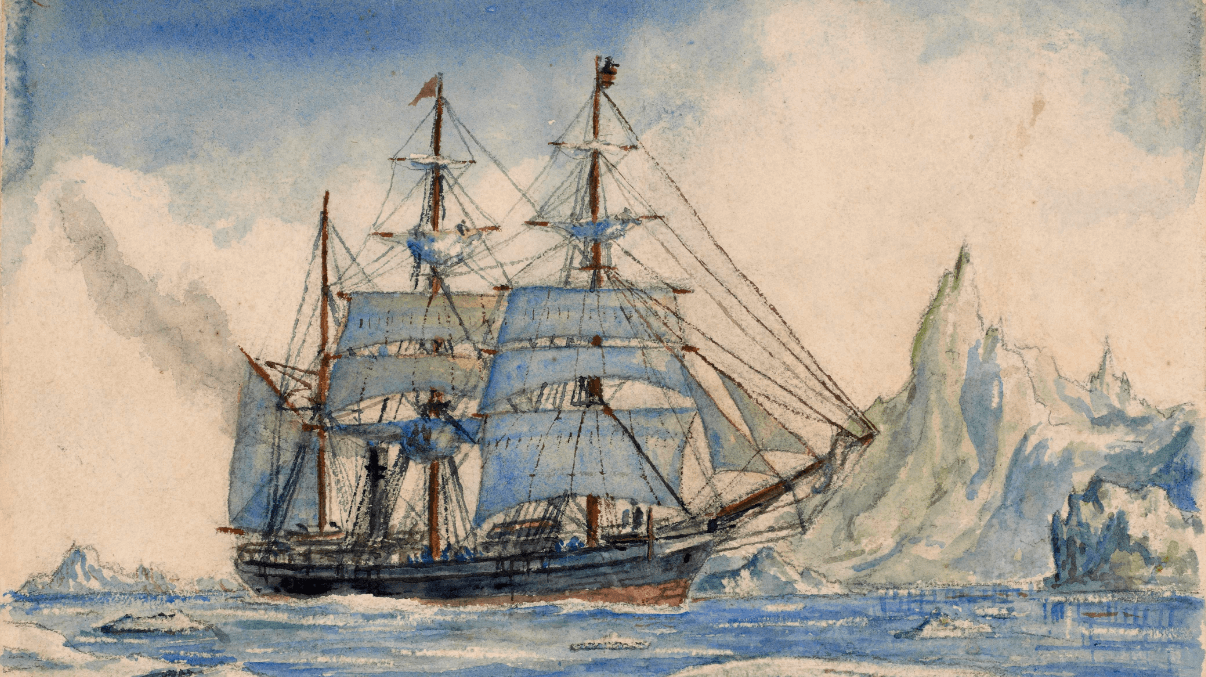

Scott’s National Antarctic, or Discovery, Expedition (1901–1904) included the first aerial survey in Antarctica by balloon. Scott, Dr. Edward Wilson, and Ernest Shackleton set out with dog teams and sledges, and they reached 82º16.5′ South — a new “furthest south” — before scurvy, frostbite, and a shortage of supplies forced them to turn back [item 45]. The antagonism that developed between Scott and Shackleton subsequently led them to mount separate expeditions [see section 7].These pictures were taken of Shackleton during Scott’s Discovery Expedition, showing his arrival in New Zealand and then, during a reconnaissance mission, the Terra Novacrashing through the flows of pack ice in an attempt to reach land. About the latter, Shackleton wrote:

“It was not long before we were in the pack ice, and our stout ship was crashing through mighty flows and even then every now and again reeling back from the shock … we were fortunate enough to penetrate farther east and discover new land … On the 19th I was given a small party to make a sledge reconnaissance of the South west in order to see what chances there were for getting to the South by sledge journeys … so we are now making preparations for the Southern trip …”

42. Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge

South America Sheet V. Patagonia

London: J. & C. Walker, 1838

43. Joseph Meyer

“Südlichster Theil von America enthaltend Patagonia, Feuerland & Falklands Gruppe”

From: Meyers-Handatlas (Hildburghausen, 1844), 13

This map summarizes the race for the South Pole, with its indications of progressive “furthest souths.” Even so, most of the continent remains in the light brown of unexplored territory. At the center, the South Pole is noted “Amundsen 90°, 14th December 1911.” The presumption is therefore that this map was printed in 1912, after news of Amundsen’s achievement reached Edinburgh, but before the heart-breaking news of Scott’s reaching the pole a month later.

44. W. and A. K. Johnston

“South Polar Chart”

From: Handy Royal Atlas (Edinburgh and London: W. & A. K. Johnston, 1912)

45. George F. A. Mulock

“Map Showing the Work of the National Antarctic Expedition. 1902–3–4”

From: Geographical Journal 24, no. 2 (1904): 201

46. Roald Amundsen

“Routes of Captain R. Amundsen’s South Polar Expedition 1911–12”

From: Geographical Journal 41, no.1 (1913): after 13

B. The Terra Nova Expedition (1910–1912)

After Shackleton just failed to reach the pole in 1909 [section 7], Scott organized the British Antarctic, or Terra Nova [item 48], Expedition (1910–1912). With four men, all hauling sledges, he followed the route pioneered by Shackleton. The party reached the Pole on January 17, 1912, only to discover the Norwegian flag that Amundsen had planted just a month before. Their return was gruesome. Five men shared rations meant for four and the weather was horrendous. Ravaged by hunger, scurvy, snow blindness, exhaustion, and injury, Scott and his four companions all perished [item 47].

A member of the search party that discovered their fate in October 1912 wrote, “… after we found the tent . . . snowed up and looking like a cairn. . . . Inside the tent were the bodies of Captain Scott, Doctor Wilson, and Lieutenant Bowers. They had pitched their tent well, and it had withstood all the blizzards of an exceptionally hard winter. . . . Wilson and Bowers were found in the attitude of sleep, their sleeping-bags closed over their heads as they would naturally close them. Scott died later. He had thrown back the flaps of his sleeping-bag and opened his coat . . . his arm flung across Wilson.”

Tryggve Gran was a member of the search party that set out to discover the fate of Scott and his companions in October 1912. He described the burial in his diary: “We buried our dead companions this morning; it was a truly solemn moment. . . . We have erected a 12-foot cairn over the graves and atop a cross made of a pair of skis.”

47. Tryggve Gran

Grave on “The Great Ice Barrier” (The Last Rest, the grave of Scott, Wilson, and Bowers), 1912

Printed by Herbert George Ponting

Having served with Shackleton, as part of the advance team that laid in the food and fuel depots for Shackleton’s nearly successful attempt to reach the South Pole in 1909, Priestley returned to the Antarctic as a member of the Terra Nova Expedition. Priestly joined eight scientists at Terra Nova Bay for eight weeks of summer fieldwork, but the Terra Nova was unable to penetrate the ice pack to retrieve them, as arranged. Realizing that they would have to winter where they were, they excavated a small, twelve-foot by nine-foot ice cave in a snow drift, nicknamed “Inexpressible Island,” where they stayed for almost seven months, supplementing their meager rations with seal and penguin. With two of the party sick they left and walked for five weeks, fortuitously finding a cache of food left the previous year. They eventually arrived safely back at Cape Evans on November 7, 1912, only to be informed that Scott and the entire Polar party had perished months earlier.

48. Raymond Edward Priestley

“The Terra Nova in the Ice Pack”

Watercolor, ca. 1910

This original studio portrait shows Scott wearing the Victorian Order and the Polar Medal from the Discovery Expedition of 1901-1904.

49. Maull & Fox

Robert F. Scott, ca. 1904–1905

Having won the tender from the British Admiralty to build a vessel for Antarctic exploration, the Dundee Shipbuilders Company laid down the keel in March 1900 and she was named “Discovery” in June 1900. Scott’s Discovery was barque-rigged. Her particular features, for ice work, included a rudder and screw which could be detached and lifted up through the deck at the stern, a massively reinforced bow whose stem was made up of blocks of scarfed wood, bolted and protected with steel plates, and heavily lined sides. She was launched by Lady Markham on 21 March 1901.

50. Dundee Shipbuilders Co.

“Rigging Plan S.S. No. 133 for Antarctic Exploration”

ca. 1900

51. Eastwood

“The Last View of the ‘Discovery’ as She Left Lyttelton, N.Z.”

From: Illustrated London News (April 4, 1903)

Both pieces of cutlery are hallmarked “RODGERS EP.” The fork is 7¼ inches long, the knife 8¼ inches.

52. Rodgers EP

Knife and fork from the wardroom of the “Discovery”

Sheffield, 1901

This is the original order form for the first and limited edition — printed in just 350 numbered copies — of the third volume of The South Polar Times, edited by Apsley Cherry-Garrard, assistant zoologist to the Terra Nova. The volume included contributions by Scott and other members of the expedition.

53. Smith, Elder & Co.

Order form for The South Polar Times

London, 1911

Scott’s corpse and diaries were discovered in November 1912. Kathleen Scott was at sea on her way to meet him in New Zealand and did not receive the news until February 19, 1913. In this letter, written hurriedly and “without sleep,” she explained that she was forwarding to the admiral a letter to him that had been left with Scott’s diaries.

“It’s a glorious record wonderfully written stirring and inspiriting to the last degree — They would have got through if they hadn’t stood by their sick — & so I am very glad they did not get through . . . The last weeks of those 3 men is a wonderful tale & save for the brutal agony of having responsibilities unfulfilled there should be no regrets. He was the last to go & at the end he writes ‘Last entry — for God’s sake look after our people’ — One wishes that [he] hadn’t worried so . . .”

54. Facsimile of an autograph letter to Admiral Sir George Egerton, early 1913

55. Robert F. Scott

Captain Scott’s Message to England

London: St. Caterine’s Press, 1913

The great photographer Herbert George Ponting (1871–1935) put the exploits and tragedy of Scott’s last expedition into haunting visual form, creating in the process a body of the world’s finest Antarctic photography. He also wrote an important narrative of his experiences aboard ship and of life on the ice [56]. Ponting preserved 825 photographic negatives from Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition between 1910 and 1912: contact prints of 449 of the photographs are included in this album [57].

56. Herbert George Ponting

The Great White South

London: Duckworth & Co., 1919

57. Herbert George Ponting

Photographs of members of the British Antarctic Expedition, 1911

Gelatin silver prints