The climax of the booster genre was John Cullum’s remarkable Map of the City of Portland of 1836. With a map that was even larger than Barnes’s first Plan of Portland in ca. 1815 and more than four times the area of the contemporary maps in the directories, Cullum augmented the now well-established local conventions with an impressive and beautifully naïve iconography. The result was a wall display that celebrated a still thriving port. Portland might have ceased to be the state capital in 1832 ~ when the seat of government was moved north and inland to Augusta, to promote settlement of the interior ~ but in recompense it was at the same time chartered as a city.

Cullum was working as an engraver and printer in Boston by 1826 (Whitmore 1884, 9). In 1832, having moved to Portland, Moody hired him to make some alterations to the plates for the chart of Portland Harbor (Section 1) and to print 170 impressions (receipt).

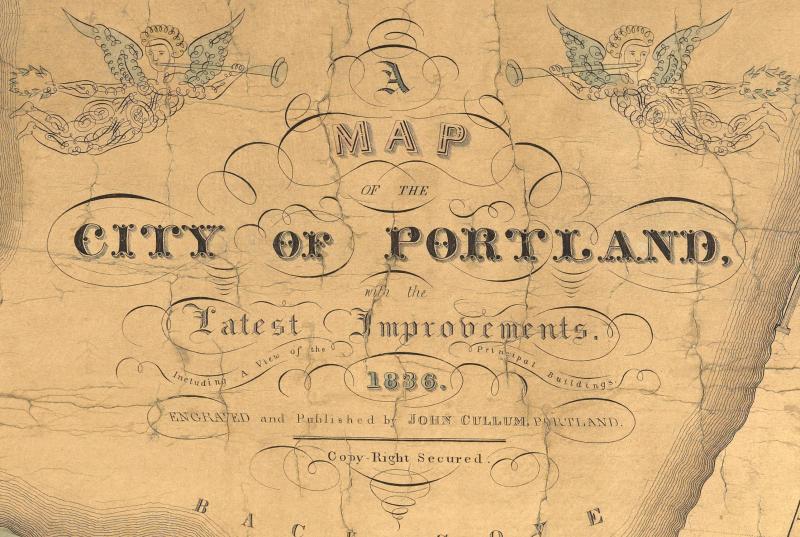

[Map 5. John Cullum, A Map of the City of Portland with the Latest Improvements. Including a View of the Principal Buildings. 1836. Engraved and Published by John Cullum, Portland. Copy-Right Secured. Copper engraving with hand-applied color, 52 x 73.5 cm. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine. OML-1836-5. (Williamson 1896, no. 2565) Click on map for high-resolution image.]

Cullum then produced this grand map. He announced its publication in the Daily Evening Advertiser for 25 October 1836 (repeated 26 October, 26 November, and 7 December):

To the Patrons of the Arts.

John Cullum, Engraver, Court Street,

Has just completed his large and splendid MAP OF PORTLAND, with faithful drawings of the several churches and other public buildings,—the whole handsomely painted, varnished and mounted. Subscribers, and others who wish to purchase, are invited to call at the Publisher’s Room, where the ENGRAVING BUSINESS, in all its branches is executed. Oct. 25.

And, elsewhere in the same issue, we find:

Cullum’s New Map of Portland—A new map of Portland has been published by Mr. Cullum. The Wards are all marked off, and colored. The streets are distinctly pointed out. All our Public Buildings are sketched off and drawn, so as not only to give strangers a good idea of the city, but so as to be a very great convenience to our own citizens. It should have a place in all our Hotels, Counting Rooms, and other places of business, and all persons will find it eminently useful.

This same advertisement also appeared in the Portland Advertiser for 1 November 1836.The map was also advertised as being “just published” in the Portland Weekly Advertiser (39, no. 4 [1 Nov 1836]).

The map’s orientation to the local community is indicated by three pieces of text. Each start in the Fore River and curve across the map to end at appropriate points of Exchange Street, to indicate three particular businesses:

John Cullum Engraver and Copper Plate Printer

Lowell & Senter’s Watch Chronometer & Jewelry Store No. 8.

S. H. Colesworthy Bookseller & Binder No. 23

It is tempting to read these concentric arcs as a statement of the details of the map’s publication: Cullum designed and printed the map; the jewelers underwrote it; and Colesworthy sold it.

The by-now conventional shading of the built-up area was slightly more expansive than on the 1831 directory map (Section 4). The title, once again, is in the Back Cove, now with ornate embellishments that literally heralded the city and its improvements:

[Detail of Map 5, but digitally enhanced to bring out the herald angels, both bearing imperial crowns of laurel, on either side of the title; the few surviving copies of this map are in poor shape and require such manipulation for clarity.]

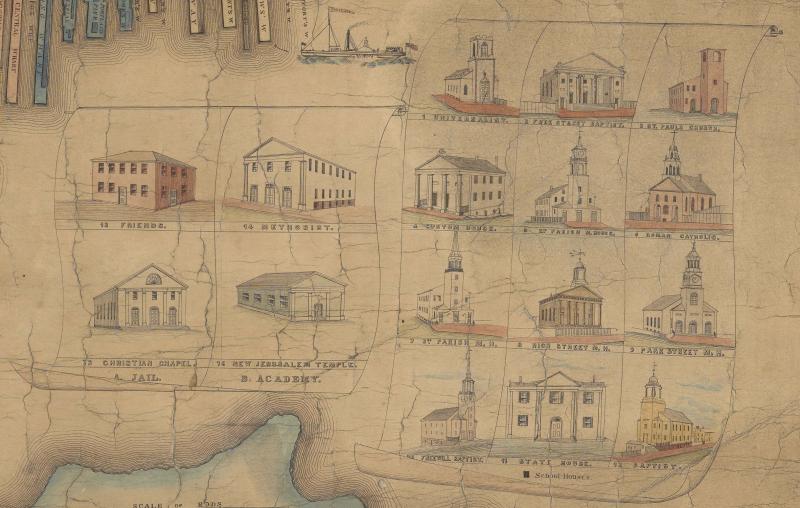

The compass rose and scrolls of references were, as required by convention, in the Fore River. The references are again numbered, but now with small vignettes of each building, producing a more complex hierarchy of institutions constituting the civitas:

[Detail of Map 5.]

The main scroll’s twelve buildings are eleven churches (1–10, 12) plus the state house (11); the second scroll displayed another four churches (13–16). In its own scroll, in the river, was the Bethel church for seamen (17); simple frames also isolated both Union Hall (18: compare with a ca. 1916 photograph) and City Hall (19), labeled with its latitude and longitude, from the river; and the Court House (25) was set by itself in a scroll offshore in the top-right corner. Then, drawn on the open land between the built-up urbs and the town’s limits, mostly on Bramhall Hill, were other institutions: two churches, specifically the First Parish Meeting House (21), relegated for some reason to this lesser tier, and the Abyssinian Church (27) built by Portland’s African-American community (begun to be built in 1828, opened for use in 1831); and a variety of commercial buildings (20, 22–24, 26, 28). Institutions away from the center were again indicated by their footprints, with the Observatory also being shown in elevation. Finally, the main scrolls indicated civic institutions that were important for the community, but not desirable for illustration: black squares for schoolhouses, plus the Jail (“A”) and Academy (“B”).

This image is of Portland, first and foremost, as an undeniably religious and moral place, with no less than eighteen different religious establishments, most grouped together for distinctive treatment. Its civic structure is evident not only in the vignettes of city hall and the courthouse, but also in the indication with large numerals, 1–7, of the wards established under the 1832 city charter. The wards were further differentiated by the application of a watercolor wash. Even so, the proliferation of vignettes across Bramhall and Munjoy hills suggests a complex design process, of a map that perhaps went through several stages. (Perhaps, at one such stage, someone had noted the absence of the First Parish Meeting House?)

Cullum’s vignettes do however point to the encroachment of national trends in urban mapping into the Portland market. Other map makers had added vignettes to their urban maps: for example, Abel Bowen’s publishing house had added, just a year earlier in 1835, delicate vignettes of buildings and streets to a map of an expansive Boston.

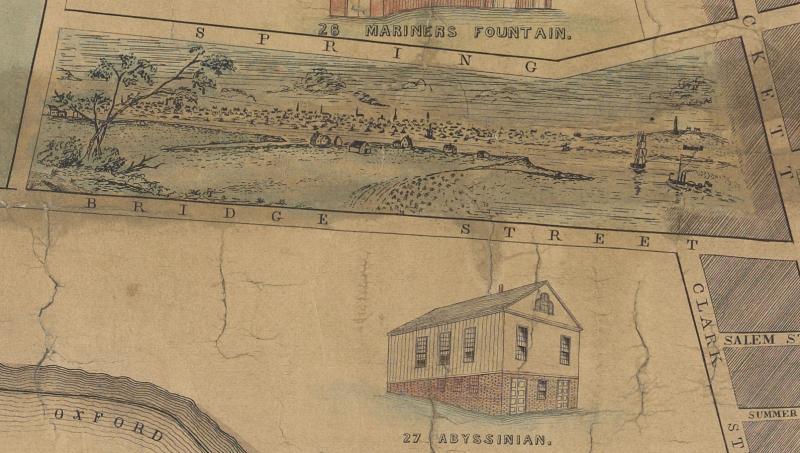

Such architectural drawings point to a different rhetoric of knowledge. Barnes’s, Bowen’s, and Johnson’s maps of Portland had variously embodied a network of streets each surveyed separately and then built up into a larger plan. But Cullum’s vignettes suggested the application of a more encompassing vision, more akin to that of the systematic topographical mapping that were flourishing in Europe and giving rise to the modern idealization of “cartography.” Indeed, uniquely, Cullum’s map included a small view of Portland, as seen from Fort Preble in Cape Elizabeth:

[Detail of Map 5.]

Cite this Page

Edney, Matthew H. “The Highpoint of the Booster Mapping.” Section 5 of “References to the Fore! Local Boosters, Historians, and Engineers Map Antebellum Portland, Maine.” www.oshermaps.org/special-map-exhibit/references-to-the-fore. Published online, 1 July 2017.